The rise and fall of the fork

For such a commonplace utensil, it is perhaps surprising that the fork is a relatively recent addition to British dining tables.

Its adoption was both emblematic of the cultural shifts around eating and a catalyst for them.

Jim and Jayne at the kitchen table with their pet cat. Pinner, Middlesex, 1962-3. Object number 168/2011-2

Jim and Jayne at the kitchen table with their pet cat. Pinner, Middlesex, 1962-3. Object number 168/2011-2

The origins of the fork

Forks have existed for centuries in one form or another throughout the world.

However it wasn't until the 10th century, in the Byzantine Empire, that they began to be commonly used at dinner tables.

And even then, their use was mostly only among the wealthy elite.

Diners in Western Europe, particularly in the British Isles, were slow to catch on to the trend.

Brits were used to getting their hands dirty with dinner: this was down to the way food was traditionally served.

The laudable use of forkes,

Brought into custome here, as they are in Italy,

To the sparing o' Napkins.

Ben Jonson, The Devil is an Ass, 1631

Fork made in Staffordshire England, c.1750-1760. Object number 1/2020-6

Fork made in Staffordshire England, c.1750-1760. Object number 1/2020-6

How we used to eat

Prior to the introduction of the fork, dinners in Britain would have been served on large communal platters on the table, with each diner helping themselves.

Individuals would have used one hand to cut the meat and the other to hold it in in place.

Table forks, if they were known of at all, were viewed as an effete, continental extravagance.

Thomas Coryat, an eccentric travel writer, misguidedly tried to persuade the English of the benefits of the fork after returning from Italy in the early 1600s. He observed:

The Italian…doe alwaies at their meales use a little forke when they cut their meat [and if] anyone should unadvisedly touch the dish of meate with his fingers from which all at the table doe cut, he will give occasion of offence unto the company, as having transgressed the lawes of good manners

Coryat's readers were unimpressed to say the least, and his acquaintances branded him with the nickname 'furcifer' (Latin for fork-bearer) as a result.

The arrival of the fork

However, the tide was starting to turn in Coryat's favour.

Hygiene became a prevalent concern for many, especially following the Great Plague of London in the 1660s.

Sharing meat between dozens of guests at a banquet no longer seemed as appetising.

Dining was shifting towards a more formal style as the home's hall began to develop into specialised and separate rooms for leisure and eating.

Meals started to be served à la française (in the French style), something akin to a modern buffet, but with the dishes placed in pre-determined elaborate displays on the table.

The fork allowed guests to help themselves without having to touch the food, and was versatile enough that it could be used to eat most dishes.

Still, use of the fork was slow to spread.

It was an expensive addition to the household – most guests were required to bring their own for both hygiene and financial reasons – and many simply preferred eating with a spoon, knife and their hands.

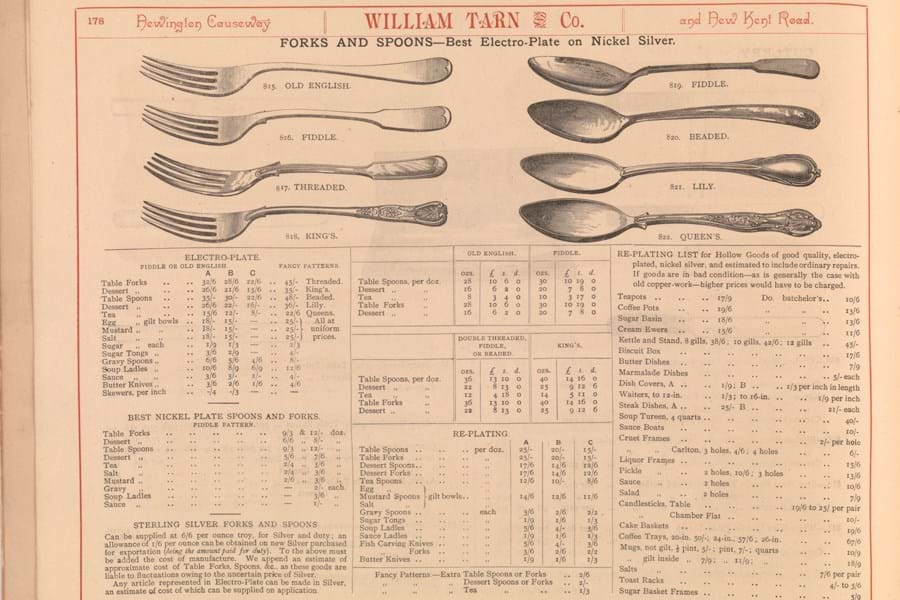

A page advertising cutlery in William Tarn and Co.'s Illustrated Catalogue. c.1890-1900. Object number 6/2005

A page advertising cutlery in William Tarn and Co.'s Illustrated Catalogue. c.1890-1900. Object number 6/2005

How the fork became a staple of British dining

Throughout the 1700s, forks became easier to produce and cheaper to buy.

At the same time, dining fashions of the upper classes gradually filtered down across society.

By the Victorian era not only was the fork a staple household item, but there was a fork designed for every conceivable use: from the sardine fork to the asparagus fork.

Dining had also shifted to service à la russe (in the Russian style), in which individual dishes were served to each guest, course by course. This style was made possible by cheap domestic labour.

Dining sets of porcelain and cutlery became a must-have for any household and remain a traditional wedding gift to this day.

Christine and several members of her family seated around a dining table in Leyton, London. c. 1968. Object number 96/2008

Christine and several members of her family seated around a dining table in Leyton, London. c. 1968. Object number 96/2008

What next?

From the latter half of the 20th century up until today, there has been somewhat of a backlash towards this highly regimented formal dining inherited from the Victorians.

Many of us now eat on our laps in front of the telly, or for parties use the informal Swedish Smörgåsbord buffet-style approach, which itself harkens back to the pre-fork era in English domestic dining.

Additionally, with the influx of different cultures and cuisines into Britain we have become used to using other utensils like chopsticks and indeed eating with our hands once again.

Domestic game changers

The objects that shaped domestic life.