German bombing raids during the Second World War killed thousands and left London’s housing stock in tatters. New builds like this terraced house in Camden rose from the ashes, designed cheaply and quickly to fill the awkward spaces left in Victorian and Georgian terraced streets.

Newlyweds Kathleen and Jack are getting ready for a big night out at the Galtymore dancehall in Cricklewood, where they first met a few years earlier.

Kathleen left Northern Ireland for a nursing job in the newly formed NHS, and Jack left his rural home in Roscommon for the plentiful construction work in post-Second World War London.

Kathleen has applied her favourite perfume Coty L’Aimant, a gift from Jack, and is hurriedly ironing his best suit so that he looks appropriately sharp on the dance floor.

Meanwhile Jack is pouring them both a drink to warm them up for the long bus ride ahead.

This room was curated with the London Irish Centre, and supported by David P. Kelly

Objects to look out for

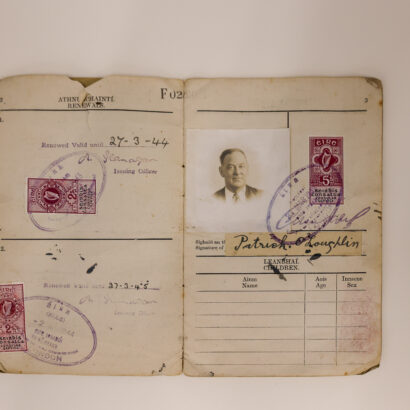

Irish ID Card

Before Patrick moved to London, he would travel between Ireland and England several times a year for work, getting his ID card stamped for each trip. This is a common story among Irish migrants, with some continuing to travel rather than settling permanently in the UK.

Irish ID, Credit: Museum of the Home

Sacred Heart Print, 1922

While some left Ireland to break away from the dominance that the Church played in people’s lives, religion was still a crucial part of life for most people in the London Irish community. Sacred Heart artworks were a staple of Irish homes, with this print handed down through generations in Tom G’s family.

Sacred Heart Print, Credit: Tian Khee Siong

Woodchip and Magnolia

A landlord’s favourite and a tenant’s worst nightmare, woodchip wallpaper provided a cheap way to cover up blemished walls that was very difficult to remove if you didn’t like it. However, one advantage was that it could be painted over, and the newly developed magnolia became a fast favourite in the 1950s.

Woodchip and Magnolia

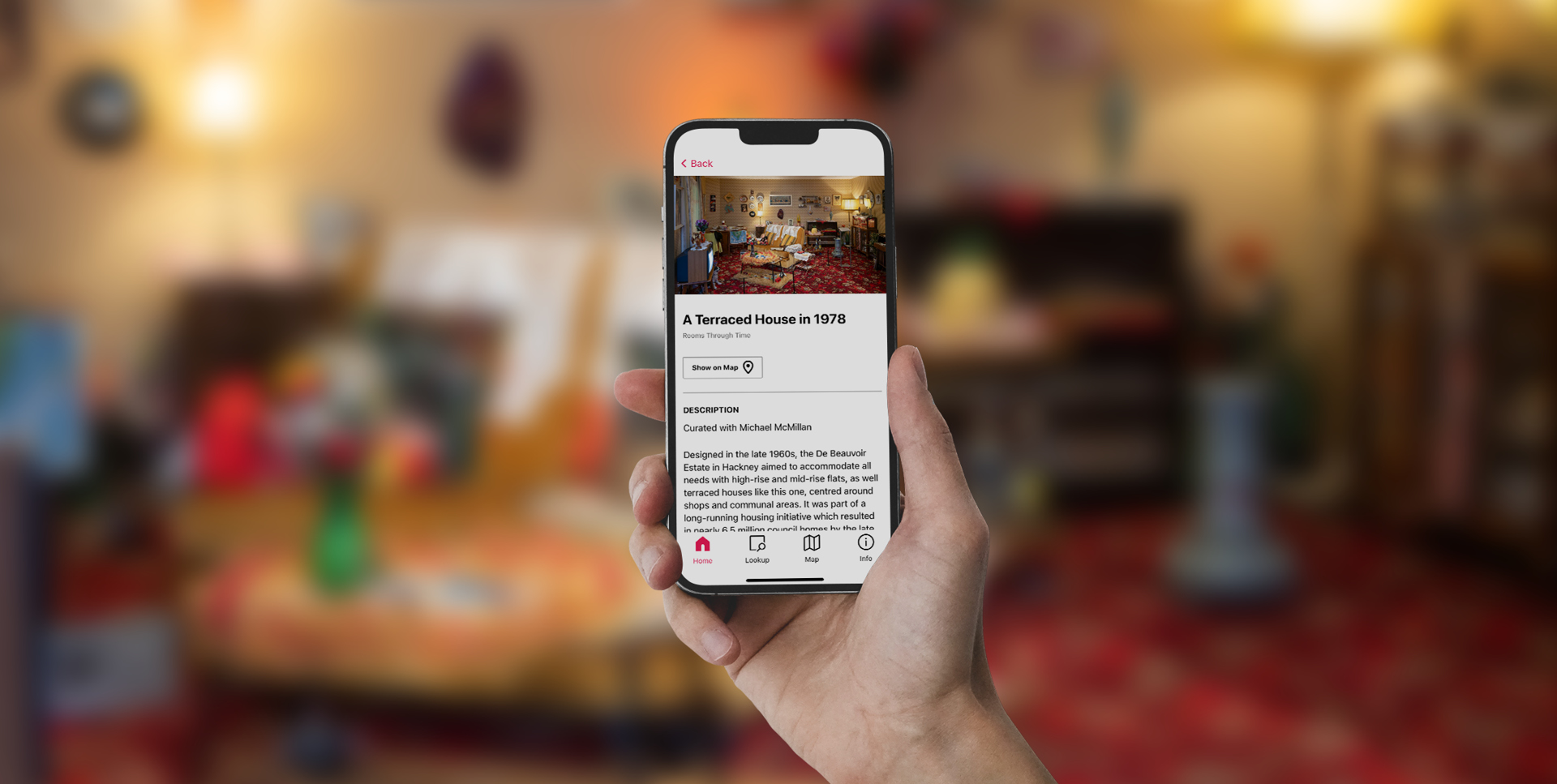

Free digital guide

Explore Museum of the Home with our digital guide on Bloomberg Connects, the free arts and culture app.